Do Google and AI really read your website? A complete guide to rendering

You can’t rank what the search engine can’t see. Have you ever thought about that? You publish a page, optimize the meta tags, and take care of the text, assuming that Google sees the content exactly as you do. Often, you’re wrong.

Between discovering the URL and its ranking, there is a mandatory technical step called rendering, which is the process that transforms the source code into the visual elements of the page. And if your site depends on JavaScript or heavy resources, Googlebot may have difficulty performing this step and indexes what it sees. Not your content, but nothing.

It is during rendering that instructions and components become a page that can be used by the engine, and this is where the hierarchy of content, its accessibility, and the weight that each element takes on in the process of understanding come from. And it is at this stage that you can and must intervene if you want Google and AI to really see what you are publishing.

What is rendering and what does it mean to render?

Rendering is the technical step that transforms the code of a web page into an interpretable version, in which resources, content, and structure take on a precise order, on which the engine builds its reading.

The term actually has multiple meanings, because it refers both to browser-side graphics rendering and to a deeper process that concerns the way in which a page becomes effectively readable for an automated system. In everyday language, the two meanings overlap; in web work, they do not. Here, rendering has nothing to do with aesthetics, but with the transformation of code into accessible, structured, and evaluable content.

In computer science, in particular, rendering refers to the operation through which a computer processes a series of encoded information to produce sensory output that is understandable to the user. It is the act of translation that converts abstract mathematical or logical instructions into pixels, sounds, or concrete interactions. Without this step, the web would be nothing more than an unreadable archive of incomprehensible text strings and scripts.

When a page depends on external resources, scripts, or dynamic constructions, what emerges after rendering can differ substantially from what was designed. Relevant parts may arrive late, others may be secondary, and still others may not be available when the engine has to decide how to interpret the page.

This is where the problem arises: SEO is not played out on the code in the abstract, but on the final version that the engine manages to reconstruct. In our case, therefore, we are talking about rendering in the context of the web and SEO, to understand how Google really sees a page and why this phase directly affects the understanding and visibility of content.

What web rendering means

The fundamental distinction you need to make is between static code, which resides passively on the server, and the rendered page, which lives actively in the browser. The HTML file you upload via FTP is just a theater script; rendering is the staging. If the director (the browser or bot) does not have the resources, time, or skills to interpret the instructions in the script—especially if they are complex or written in a dynamic language such as JavaScript—the show does not happen. The page remains untapped potential and, for the search engine that has to judge it, is equivalent to an empty stage.

Going into technical detail, rendering means performing a state transformation. The browser receives a series of raw bytes from the server that represent code (HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, fonts). These bytes have no intrinsic form: they are not “blue,” they are not “top right,” they are not “interactive.” It is the browser’s rendering engine (such as Blink for Chrome or WebKit for Safari) that must take on the burden of analyzing (parsing) these instructions, building a logical map of the relationships between the elements, and finally “painting” (painting) the pixels on the device’s screen.

Every time a user visits your site, their device is performing millions of calculations to decide where to place each letter and what color to paint each pixel. This computational effort is not free: it requires CPU, RAM, and energy. When the site is built with modern technologies that modify content in real time using JavaScript, rendering ceases to be a one-time operation and becomes a continuous process. The browser does not simply “read” the page, but must “execute” an actual program to generate the content. If this program is too heavy or poorly optimized, the translation process jams or slows down, compromising the final experience.

Areas of application: from gaming to web rendering

It is also important not to confuse Web Rendering, which we deal with in the field of SEO, with other forms of graphics processing such as 3D rendering used in video games or film post-production. Although the basic principle is the same — translating information into a form that is immediately accessible, understandable, and usable for those who use it — the purposes and technologies are radically different.

In the field of graphic design, in particular, rendering is used to create highly realistic visual representations of three-dimensional objects. Think of the creation of objects in animated films or video games: three-dimensional digital models are created, which then have to be “rendered” to appear on the screen in detailed form, with textures, lights, and shadows, in a way that is almost indistinguishable from reality. This process requires complex algorithms that transform raw data into high-resolution images, and the quality of the rendering can make the difference between smooth, immersive animation and graphics that appear artificial and unconvincing. Architectural rendering is another context in which you often hear this term used: architects create 3D models of buildings and landscapes, visualizing them with high precision using rendering software that adds details such as materials, ambient lighting, and even weather conditions to provide a realistic preview of how the projects will look once built.

Finally, there is a more recent application of rendering in the field of Big Data and data visualization, where numbers do not provide immediately understandable information unless they are translated into graphs and visual diagrams. Here, too, numerical data is “rendered” into visual form, allowing users (whether experts or novices) to quickly interpret and understand complex data.

In gaming, the priority is visual fluidity and realism, which are mainly managed by the video card (GPU). On the web, the priority is the semantic structure and accessibility of information, which are mainly managed by the processor (CPU) through the construction of the DOM (Document Object Model, the logical structure of the page).

When we talk about technical SEO, we refer exclusively to the ability of User Agents (the software that navigates the web, whether human browsers or search engine crawlers) to complete the web page construction cycle. Our battlefield is not graphic resolution, but the architecture of information. We must ensure that text, links, and metadata—which are the “meat” of positioning—are generated correctly from the source code. If a search engine, which does not have a powerful graphics card but operates in a simulated and minimalist environment, fails to replicate the Web Rendering process, your site loses its primary function as a vehicle for information.

The risk of invisibility for a site

Here we get to the heart of the problem that defines modern SEO. There is a dangerous discrepancy, often invisible to the naked eye, between what a human user sees and what a bot sees. A user browsing with the latest version of Chrome on a powerful computer has almost unlimited resources to wait and execute heavy scripts. If a page takes three seconds to load the main text via JavaScript, the user waits. Google’s bot, on the other hand, operates with very tight time and resource constraints.

This asymmetry creates the paradox of technical invisibility. You see the site working perfectly, colorful and full of products, because your browser has completed the rendering. Googlebot, on the other hand, may have stopped before JavaScript injected the content into the DOM, effectively seeing a blank page or one lacking the essential elements for ranking.

This is why we talk about invisibility: technically, the content exists in the database and is served to the user, but for the search engine, it has never been “materialized.” Understanding this disconnect between the source code (what the server sends) and the rendered DOM (what the user sees) is the first step in diagnosing and solving ranking problems that no keyword optimization can ever fix.

Essentially, even if you don’t deal with technology and code, you need to have at least a basic understanding of this process because rendering is important and provides the truth.

Through code, a search engine can understand what a page is about and approximately what it contains. With rendering, they can understand the user experience and have much more information about which content should be given priority.

During the rendering phase, the search engine can answer many questions that are relevant to properly understanding a page and how it should be ranked, such as:

- Is the content hidden behind a click?

- Does an ad fill the page?

- Is the content displayed at the bottom of the code actually displayed at the top or in the navigation?

- Is the page slow to load?

The history and evolution of rendering

To understand why you now have to deal with abstruse concepts such as “partial hydration” or “resumability” just to get Google to read a page, you need to take a step back. The current complexity is the result of a long power struggle between the server and the browser and the oscillation between two extremes—centralized computing power and user interface agility. And SEO has always been forced to play catch-up, trying to adapt to standards that were rewritten every five years.

Until the early 2000s, the web was a technically honest place. There was only one truth: static HTML. At this stage, rendering was the exclusive domain of the server. When a user clicked on a link, the server crunched the data, built the entire page, and sent it to the browser. The client was a passive executor.

For those of us who do SEO, it was heaven: what the user saw was exactly what the crawler saw. The source code was transparent, readable, immediate. The price to pay, however, was a fragmented user experience: every interaction required a complete reload of the page, with that annoying white screen in between that broke the flow of navigation.

Everything changed when developers decided to eliminate that wait. With the advent of AJAX first, and the explosion of frameworks such as Angular and React later, we moved the brain of the operation from the server to the user’s device.

The era of Single Page Applications (SPAs) was born. The server stopped sending web pages and became a simple distributor of raw data (JSON). The task of building the interface, placing images, and writing text was entirely offloaded to the user’s browser via JavaScript.

For the User Experience, it was a revolution—sites as fluid as native apps; for SEO, it was a catastrophe. Suddenly, Googlebot was faced with empty shells. The content was gone; there was only code that promised to generate it. It was at this historic moment that the JavaScript “black box” was born, along with the desperate need to understand if and when Google was executing scripts.

We soon realized that the pure SPA model was unsustainable: users’ phones were overheating to perform rendering, and search engines were losing too much content along the way.

The industry responded by creating the hybrid monsters we use today (such as Next.js or Nuxt). We went back to generating HTML on the server to please Google (SSR), but as soon as the page arrives on the browser, we “inject” tons of JavaScript to make it interactive like an SPA.

This process is called Hydration, and it’s the cause of your current problems with Core Web Vitals. We’re forcing the browser to do the work twice: first it displays the static HTML, then it has to re-execute all the code to “hook” the interactive events. It’s a technological patch that saves indexing, but often kills the INP (Interaction to Next Paint) metric.

Today, we are finally trying to get out of the hydration trap. New architectural frontiers are pointing towards Resumability (with technologies such as Qwik): the idea is that the server does all the work and sends the browser a “paused” application, ready to resume execution instantly without having to download and re-read all the JavaScript.

At the same time, the very concept of “server” has evaporated. With Edge Rendering, rendering no longer takes place in a distant data center, but is performed in fragments on hundreds of CDN nodes physically close to the user. The historical pendulum is stopping in the middle: maximum computing power (server-side), but geographically distributed as if it were local. For SEO, this is the future: instant speed and perfect readability, without compromise.

Rendering keywords: definitions and metrics

Before delving into more technical explanations, following the advice of the experts at web.dev, it is useful to align ourselves on the precise terminology related to this process, because confusing one acronym with another today means getting your architecture strategy wrong. Here are the essential “keywords” for navigating modern rendering:

- Server-side rendering (SSR). The server generates the entire HTML page before sending it to the browser. This is the “traditional” technique that guarantees maximum indexing by search engines, as the content is immediately readable, but it requires a powerful server infrastructure to handle the load of each visit.

- Client-side rendering (CSR). The server sends an empty “shell” and delegates the task of downloading and executing JavaScript to build the page to the user’s browser. It offers a smooth, app-like experience, but risks showing blank pages to bots if the rendering fails or times out.

- SSG (Static Site Generation). HTML pages are built “cold” during the site build phase and saved as static files. It is the fastest architecture for loading, but it is rigid: it requires a complete rebuild to update even a single piece of content.

- ISR (Incremental Static Regeneration). The hybrid solution that combines the advantages of SSR and SSG. Pages are served as static (very fast), but the server regenerates and updates them in the background at regular intervals or when data changes, ensuring freshness without sacrificing performance.

- ESR (Edge Side Rendering). The modern evolution of distributed rendering. Page construction does not take place on the central server, but on the CDN nodes physically closest to the user. This eliminates network latency and allows dynamic content to be served at the speed of static content.

- Hydration. This is the critical process in which JavaScript “hooks” into a static HTML page (generated via SSR or SSG) to make it interactive. This is often when bottlenecks in user-perceived performance occur.

- Prerendering. The execution of a client-side application during the compilation phase to capture its initial state as static HTML. It is used as a “patch” to make Single Page Applications, which would otherwise be invisible, digestible to search engines.

From a performance perspective, the metrics that currently judge the quality of your rendering are:

- Time to First Byte (TTFB). The time that elapses from the click to the arrival of the first bit of data. If you use SSR and the server is slow, this value explodes and penalizes your ranking.

- First Contentful Paint (FCP). The exact moment when the first content (text or image) becomes visible. If rendering is blocked by heavy scripts or CSS, FCP deteriorates dramatically.

- Interaction to Next Paint (INP). The key metric for 2026, which has replaced the old FID. It measures responsiveness: if the user clicks and the site does not respond because the browser is busy executing (or hydrating) JavaScript, the INP rises and signals a poor user experience to Google.

How a web page is rendered

The rendering of a web page is the result of a sequence of steps that begins when the engine requests the URL and ends when the page takes on a complete and interpretable form. It is not an instantaneous or uniform operation: it depends on how the page is constructed, what resources it uses, and how its structure is distributed over time.

The process starts with the retrieval of the initial HTML. This first response contains the basic structure of the page, but rarely coincides with the final content. The code contains references to style sheets, scripts, and external resources that must be loaded and processed before the page can be considered complete.

During this phase, the engine downloads the necessary resources and begins to execute the scripts. This is where many modern pages change shape. Parts of the content are added, modified, or reorganized based on the result of JavaScript execution. Elements that were not present in the initial HTML may only appear at this point, while others remain suspended until certain conditions are met.

Rendering ends when the page reaches a stable configuration, where its structure and content are available for analysis. This is the “page as seen by Google”: not a snapshot of the source code, but a representation built downstream of all the necessary steps. If some elements are not loaded or remain inaccessible, they are simply not part of what the engine can interpret.

However, you should not think of this as a single, instantaneous event. Google does not guarantee that all resources on a page will be processed at the same time, nor that the rendered version will always be the “final” version intended by the site designer.

In many cases, the engine works on a progressive representation of the page. An initial version can be analyzed before complex scripts are executed or dynamically built content becomes available.

If relevant parts only emerge at a later stage, they may not immediately contribute to the understanding of the content.

This means that the evaluated page may be an intermediate version, consistent from a technical point of view but incomplete from an informational point of view. This is where a difficult-to-detect discrepancy arises: the content exists, but it is not present when the engine has to interpret the page and classify it.

The physics of the browser: the critical rendering path

You don’t need to be an engineer to see the mechanics of rendering in action; you just need to carefully observe what happens on your screen every day. Have you ever noticed that micro-instant of absolute white between clicking on a result and the page appearing? Or that annoying moment when you can see the text but can’t click on anything because the site is “frozen”?

Those delays are not random. They are the visible manifestation of a physical law of the web, the critical rendering path.

The browser is not a magic viewer that displays the page all at once; it is a worker that executes orders in a rigid and mandatory sequence. It cannot move on to the next phase until it has completed the previous one. This assembly line is what determines whether your site will be fast, slow, or even invisible.

The critical pipeline and the construction of the rendering tree

The browser’s first job is purely structural. As soon as it receives data from the server, it must transform that raw code into something that has a logical form.

It starts by reading the HTML to build the DOM (Document Object Model). You can think of this as the skeleton of the page: the browser understands that there is a title, a paragraph, and an image, and defines how they are related to each other, performing tokenization to transform the tags into nodes of a hierarchical tree.

The DOM is a style-independent structure: it contains all the elements of the page, even those that should not appear visually, but it remains a bare, invisible skeleton.

At the same time, it must read the graphic instructions to create the CSSOM (CSS Object Model), which reports the graphic appearance of the elements, such as colors, margins, and fonts. This is the “dress”: it tells the browser that the skeleton must be a certain number of pixels high, colored blue, and positioned on the right.

This is where the first major bottleneck arises: the browser will never draw a pixel until it has combined the skeleton (DOM) and the dress (CSSOM) into a single map called the Render Tree, which is the definitive structure that guides the browser through the subsequent stages of layout and drawing. The technical rule to remember is that the Render Tree includes only what is visible, and that CSS is a “blocking” resource; if a node in the DOM has a CSS rule that hides it, that node is excluded from the rendering tree. Or, if your server is slow to send style sheets, you are forcing the user (and the bot) to stare at a blank screen, even though the HTML text has already been downloaded in its entirety.

This has direct implications for indexing: although Googlebot reads the source code, content excluded from the Render Tree has zero or drastically lower semantic weight, as the engine is programmed to ignore what the user does not see.

Main thread and JavaScript, the bottleneck

Once the map is ready, the actual page must be built. The browser must calculate the exact geometry (layout) and finally color the pixels (paint). While HTML and CSS are processed relatively smoothly, JavaScript represents a brutal interruption of this flow. It is called “parser blocking” because its discovery forces the browser to stop building the DOM. When the parser encounters a script tag, it must suspend all other operations, download the file, compile it, and execute it before it can resume reading the rest of the page.

The problem is exacerbated by the single-threaded architecture of browsers. Almost all of the work takes place on the Main Thread, a single processing channel through which HTML parsing, style calculation, script execution, and user input management must pass. If you serve Googlebot a monolithic JavaScript bundle, you are saturating this single channel.

Googlebot uses the V8 engine to compile and execute code. This operation has a very high CPU cost compared to simply decoding an image or text. If the Main Thread is blocked for seconds due to a tracking script or an unoptimized framework, the crawler may decide to stop the process to save resources, leaving the page only partially indexed. Modern browsers attempt to mitigate the problem with the Preload Scanner, a lightweight process that scans the document in advance to download critical resources in the background, but this does not solve the block caused by the actual execution of the code.

This is where modern technical SEO comes into play. When the browser encounters a JavaScript file, it has to stop everything else: it blocks the page construction, downloads the script, compiles it, and executes it. As long as JavaScript occupies the lane, the browser is paralyzed: it doesn’t draw, respond to clicks, or scroll. If your scripts are heavy, the page remains blank or frozen. For Googlebot, this is a red flag: if execution requires too many resources, the bot stops working and leaves before the actual content appears.

How Google’s Web Rendering Service works

Forget the romantic idea of Googlebot “browsing” your site like a human user would, appreciating its design or animations.

The industrial reality is much colder and more efficiency-oriented. Google has to scan hundreds of billions of pages every day, and to do so on this scale, it cannot use full desktop browsers for every single URL, but relies on a massive infrastructure called the Web Rendering Service (WRS).

The WRS is based on a headless version of Chromium. “Headless” literally means “without a head”: it is a Chrome browser in all respects, capable of executing JavaScript and modern layouts, but without a graphical interface. It does not “see” colors for aesthetic pleasure, but calculates the position of pixels only to understand whether an element is visible or hidden, whether a link is clickable or covered by a pop-up.

The heart of the system is Blink, the rendering engine that manages the layout and pixel design. It is the same engine found in Chrome, Edge, and Opera. If your site has display issues on Safari (which uses WebKit), Google doesn’t care; but if rendering fails on Chrome/Blink, your site is invisible for ranking. Even more important is V8, which compiles and executes JavaScript. It is the most powerful engine on the market, but it has specific physical limitations. If your code is poorly written and causes the CPU to loop, V8 will interrupt execution to protect the crawler’s resources.

This system is designed with a single goal in mind: to extract information while expending as little energy as possible.

Limited resources and render budget

The difference between your computer and the WRS is the available power. While your PC can dedicate gigabytes of RAM and multi-core processors to load a heavy site, the Googlebot instance visiting your page has limited resources. Imagine that the bot is browsing with the capabilities of a mid-range smartphone from a few years ago.

This introduces the concept of render budget. Google assigns each page a finite amount of time and computing power: if your JavaScript code is inefficient, creates infinite loops, or takes too many seconds to process, the WRS cuts the power. It stops the script from running to save resources and moves on to the next URL. The result for you is disastrous: the bot only indexes what it has managed to render up to that point. If your main content, related products, or prices were loaded by that interrupted script, they simply don’t exist for Google.

The rendering queue

Historically, it was believed that Google indexed HTML immediately and JavaScript weeks later (the famous “two waves”). Today, Google has drastically reduced this latency, but the technical distinction remains and becomes critical during times of high traffic or for very large sites.

When Googlebot discovers a URL, it performs an immediate scan of the raw HTML code (the one sent by the server). If it finds content here, everything is fine. But if it detects that the page is empty and depends on JavaScript to display the text, it must put the URL in a Render Queue, a real waiting room, where it remains until the WRS has free resources to process it. This means that between the moment Google knows your page exists and the moment it sees what is written on it, some time may pass.

The risk today is not so much the delay as the timeout. If the script takes too long to execute or generates errors, the WRS cuts the process short and indexes only what it has seen up to that point. For a JS-heavy site, this often means ending up in the index with a blank page or without navigation links. For a news site that needs to be indexed in minutes, or an e-commerce site that changes prices quickly, ending up in the rendering queue is a huge business risk: your content is online for users, but invisible or obsolete for the search engine.

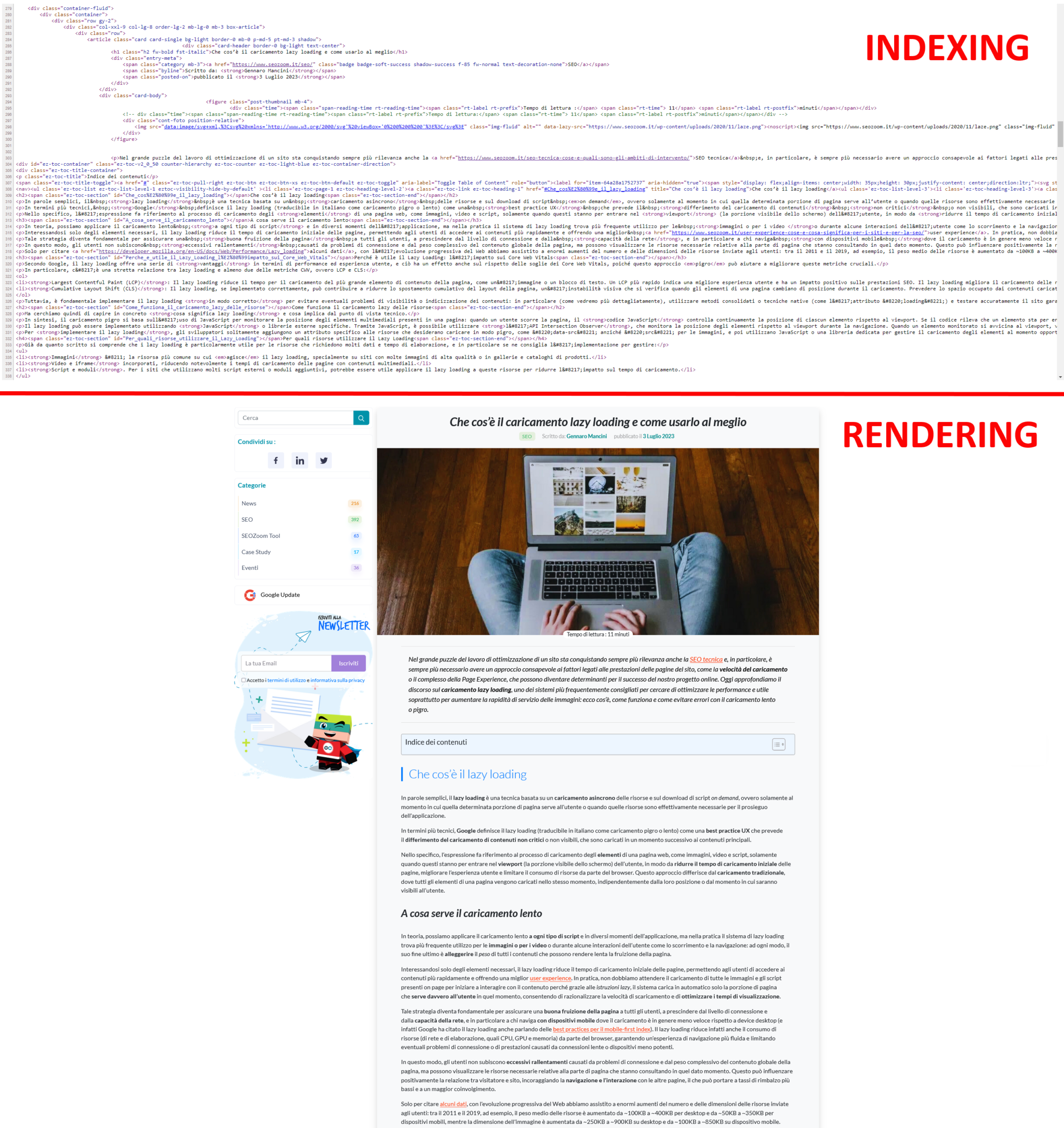

This happens for a “simple” reason, which is clear and obvious when you look at the two images below: at the top, you see the lines of HTML code for a page on our blog, while at the bottom is the graphical representation of the same page as it appears in the browser. Essentially, it is the same content, first shown as it appears during indexing (HTML) and then as it is rendered (Chrome). So, you can think of rendering as the process in which Googlebot retrieves the pages of your site, executes the code, and evaluates the content to understand its layout or structure. All the information collected by Google during the rendering process is then used to rank the quality and value of the site’s content relative to other sites and what people are looking for with Google Search.

Rendering according to Google: the analogy with recipes

To better understand how Google handles rendering, think about what happens when you prepare a recipe, using an analogy devised by Googler Martin Splitt.

Google’s first wave of indexing is like reading the list of ingredients in a recipe: it gives Google a general idea of what the page contains. However, just like when you read a list of ingredients, you don’t get the full picture of the finished dish.

That’s where Google’s second wave of indexing comes in, which is like following the steps in the recipe to actually prepare the dish. During this second wave, Google executes JavaScript to “prepare” the page and display JavaScript-based content. However, just as preparing a recipe can take time, Google’s second wave of indexing can also take time, sometimes days or weeks.

From an SEO perspective, rendering is critical because it determines how and when your site’s content is “served” to Google and, consequently, how and when it appears in search results. If parts of the ‘dish’ (i.e., your website) are JavaScript-based and therefore require Google’s second wave of indexing to be “prepared,” they may not be immediately visible in search results.

To ensure that the “dish” is ready to be served as soon as Google reads the “ingredient list,” you can use techniques such as server-side rendering (SSR) or pre-rendering, which prepare the page in advance, generating a static version that can be easily “tasted” by Google during its first wave of indexing.

Furthermore, just as a chef would do taste tests while preparing a dish, you should regularly test your site with tools such as Google Search Console to ensure that Google is able to “taste” and index your content correctly.

Rendering in the age of AI and GEO

Rendering optimization has taken on a new urgency with the advent of GEO (Generative Engine Optimization) and the spread of AI-based response engines (such as SearchGPT, Perplexity, or Google’s own AI Overview). If until yesterday your goal was to convince a classic crawler to index you, today you have to convince an LLM (Large Language Model) to read and cite you. And these new “synthetic users” are even more demanding in terms of code cleanliness and execution speed, because they operate with an even smaller tolerance window than Googlebot.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems must scan, understand, and rework information in real time to respond to the user waiting in chat. While Google can technically afford to queue a page and come back after a few minutes, an AI engine that has to respond now cannot tolerate latency. If your content depends on heavy JavaScript and is not immediately available in the initial DOM, the AI discards it as “noise” and moves on to the next source, excluding you from the conversation before it even begins.

Machine readability and token economy

There is an economic aspect that is often overlooked: reading code costs money. Language models “pay” for information processing in tokens. A heavy page, cluttered with unnecessary JavaScript or requiring complex rendering, consumes more tokens to be deciphered. AI search engines are designed to maximize efficiency: they prefer sources that offer high information density at a low extraction cost.

A site optimized with server-side rendering (SSR) or static site generation (SSG) offers AI a “ready-made meal”: clean, structured, immediately digestible text. Conversely, a CSR site forces the model to simulate a browser, execute scripts, and wait for loading, exponentially increasing the computational cost of data acquisition. In GEO logic, facilitating rendering means breaking down barriers to entry for algorithms, increasing the likelihood that your content will be chosen as an authoritative source for building the synthetic response.

The risk of hallucination on dynamic content

The most insidious danger of poor rendering in the AI era is hallucination or misinterpretation. If an LLM attempts to read your page but JavaScript rendering partially fails, it may encounter inconsistent text fragments, unpopulated variables, or empty placeholders (e.g., reading {{product_price}} instead of $100).

Unlike the old Googlebot, which would simply ignore the page, a generative model might attempt to “fill in the gaps” based on statistical probability, effectively inventing information that does not exist on your site, or it might associate your brand with incorrect data. Ensuring robust and deterministic rendering ensures that AI reads exactly what you have written, protecting the integrity of your message and the reputation of your brand in automated responses.

Rendering architectures: strategies and costs

Once you understand the mechanics of the browser and Google’s limitations, you need to make a strategic decision: which architecture to use for your project? Beyond the purely technical aspect, this becomes a business decision that determines who will pay the computational “bill” for rendering. Each architecture shifts the workload—and therefore the cost in terms of time and energy—to a different actor: your server, the user’s device, or the search engine bot.

Essentially, you have three options: pass this cost on to your server (paying for infrastructure), pass it on to the user (risking that their device will be slow), or try to pass it on to Google (hoping that the bot has the time and inclination to do so).

Choosing the wrong architecture means sabotaging your SEO at its core, because the dynamic we have just described takes on critical contours when the “visitor” is not a human with the latest generation iPhone, but a search engine crawler that has to scan billions of pages a day with limited resources. If you entrust all the work to the client (Googlebot) hoping that it has the resources to do so, you are betting your visibility on a variable that you do not control—you are asking the search engine to invest its CPU resources to build your page before even knowing if it deserves to be indexed. It’s an asymmetric bet where the house always wins: if the rendering cost exceeds the tolerance threshold or the budget allocated to your site, Google cuts off funding. The process is terminated, the page remains blank, and the content invisible.

On the other hand, if you move everything to the server, you gain indexing security but must be prepared to bear higher infrastructure costs and manage potential slowdowns in the initial response. There is no such thing as a perfect solution; there is only the one that best suits your positioning goals and the type of content you offer.

The stability of server-side rendering

Server-side rendering is the classic approach and, from an SEO perspective, the most conservative and secure—if your priority is absolute certainty of indexing, this is the only viable option. In this configuration, when a request arrives, the server does all the heavy lifting: it queries the database, processes the logic, populates the template, and packages a complete, ready-to-use HTML page.

The browser (or Googlebot) receives a document that already contains all the text, links, and significant metadata from the very first byte, in the initial payload, without having to activate the V8 JavaScript engine to find out what the page is about or what the internal links are.

The strategic advantage is the elimination of the risk of client-side rendering. Googlebot does not have to wait or run complex scripts to understand what the page is about; the information is there, immediate and accessible. This maximizes scannability and ensures that content is indexed quickly.

The other side of the coin is that the server has to generate a new page for every single request, making the system vulnerable to traffic spikes and database inefficiencies—and if you have a lot of traffic or complex database queries, the server may take a few moments before it starts sending data, slowing down the initial perception of speed. A slow backend immediately translates into a high Time to First Byte (TTFB), creating a paradox where the content is theoretically readable but the bot reduces its crawl frequency because the server responds too slowly, interpreting the delay as a sign of infrastructure suffering.

The technical debt of client-side rendering

Client-Side Rendering (CSR) represents the opposite extreme, where the server simply sends an empty container (often a blank page with a single script) and delegates the construction of the interface to the browser.

It is the standard for many modern web applications based on frameworks such as React, Angular, or Vue. Although it ensures smooth navigation for the human user, it presents a formidable obstacle for a crawler. You are asking Googlebot to do the dirty work, to complete the execution of the code without errors and within the timeout: if the WRS does not have sufficient resources, if the script times out, or if there is a JavaScript error, the page remains blank. There is no backup HTML version.

Although Google has become very good at executing JavaScript, relying on pure CSR for pages that need to rank (such as blog articles or product listings) is an unnecessary risk. Field data shows that CSR introduces unacceptable volatility for business-critical pages. If a script fails to execute, perhaps due to an unhandled exception or the bot running out of memory, the page dies. Furthermore, CSR slows down the discovery of new content: Google has to scan the URL, queue it for rendering, execute it, and only then can it find new links to follow. This structural delay makes CSR unsuitable for news or e-commerce sites that require rapid indexing.

However, it is the perfect choice for restricted areas, user dashboards, or SaaS tools where indexing is not necessary and fluid interactivity similar to a native app is preferred.

Hybrid solutions and the evolution of SSG, ISR, and Edge

To overcome the dichotomy between “slow server” and “risky client,” web engineering (especially with the JAMstack architecture) has developed hybrid models that seek to decouple rendering time from request time.

Static Site Generation (SSG) moves rendering to an even earlier stage, the build phase; the server generates all possible HTML pages before the user even arrives on the site, creating static files that eliminate real-time CPU load. When the request arrives, the file is already ready to be served instantly. It is perfection in terms of speed and SEO security, but it is rigid: if you change a price or correct a text, you have to rebuild the entire site, which is detrimental, especially if you manage large volumes of data.

The dynamic evolution is Incremental Static Regeneration (ISR), designed primarily for complex projects. This technology allows you to serve static pages (fast and secure for the bot) but regenerate them in the background at regular intervals or when the data changes. In practice, you get the security of SSR (Google sees pure HTML) with the speed of static, without having to rebuild the site for every comma changed.

The most advanced frontier, Edge Rendering, further shifts execution from centralized servers to the peripheral nodes of a CDN. This allows you to customize content dynamically without the latency of the origin server and without the risks of client-side rendering, as the bot is still delivered HTML that is already rendered and ready for indexing.

Common rendering errors and search engine-unfriendly programming patterns

There is a structural divergence between modern frontend development best practices and the strict crawlability requirements of a crawler. While the JavaScript ecosystem, driven by frameworks such as React or Angular, pushes towards abstraction and client-side state management to maximize interface responsiveness, Googlebot needs static, declarative anchor points to navigate the structure. This conflict creates a frequent paradox: websites that are technically flawless, free of functional bugs, and lightning fast for human users are completely invisible or “flat” to the search engine.

The problem lies in the use of imperative logic to manage functions that should be declarative. When a developer replaces the semantic structure of HTML (which explains what an element is) with JavaScript instructions (which explain what to do when interacting with it), they are building a maze to which Google does not have the key. The crawler is programmed to extract information from the document structure; if this structure is only revealed after complex events have been executed, the flow of authority between pages is interrupted. These are not simple code errors, but architectural patterns that sabotage content discovery, wasting the crawl budget on resources that do not lead to indexable pages.

Interruption of the internal link graph

The most common and devastating error in Single Page Applications is the simulation of navigation through JavaScript events. For convenience or to manage animated transitions, developers tend to use generic elements such as div, span, or button associated with onclick listeners to change course and load new content without reloading the page.

Although the user perceives this behavior as normal, like a URL change, for Googlebot that element is a dead end. The crawler builds the site graph by following only standard anchor tags with a valid href attribute. Any other form of navigation is ignored when building the link map.

To see the error, note the syntactic difference between an imperative command and a semantic reference.

- The invisible patter (Bad Practice)

<div class=”button-nav” onclick=”window.location.href=’/products/shoes'”>

Discover the collection

</div>

In this case, the crawler only sees a generic container (div) with text. The navigation instruction is hidden inside a JavaScript event that the bot does not activate to discover URLs.

- The scannable pattern (Good Practice)

<a href=”/products/shoes” class=”button-nav”>

Discover the collection

</a>

When a developer uses a pattern such as <div onclick=”window.location.href=‘/products’”>…</div>, they are instructing the browser on how to react to a click, but they are not declaring the existence of a relationship between two pages. For Googlebot, that div is an inert container with no destination, as the engine does not perform speculative actions such as clicking on every element on the page to see if something happens. Conversely, using the semantic tag <a href=”/products”>…</a> creates an explicit arc in the site graph. Even if the interaction is then intercepted via JavaScript to manage a smooth transition (typical behavior of Single Page Applications), the presence of the href attribute ensures that the path exists in the static DOM. This allows the crawler to extract the URL and add it to the scan queue regardless of whether the navigation scripts execute or fail, ensuring the continuity of PageRank.

Incorrect management of the viewport and deferred resources

The second error concerns the implementation of Lazy Loading, which hides critical pitfalls if it is not calibrated to the mechanical behavior of the bot. Many third-party libraries activate the loading of resources (images, but often also entire sections of text, review widgets, or related products) by intercepting the user’s physical scroll event.

Googlebot does not interact with the page by scrolling it like a human being. The Web Rendering Service simulates the display by vertically resizing the virtual viewport (often set very high) to check the responsive layout, but does not generate continuous scrolling events. If the trigger for loading content is strictly bound to mouse movement or active scrolling, deferred content will never be rendered during crawling.

It is imperative to use the native IntersectionObserver browser API or the standard HTML attribute loading=”lazy,” which are fully supported and correctly interpreted by the crawler as a signal to load the resource without requiring simulated physical interactions.

Proper implementation requires the use of the native HTML5 attribute that delegates the loading decision to the browser, bypassing third-party libraries based on scroll events.

An example of native (SEO-friendly) implementation is

<img src=”products-HD.jpg” loading=”lazy” alt=”SEO Description” width=”800″ height=”600″>

This code is universal. Googlebot interprets it correctly and knows that the image exists, even if it does not download it immediately. On the contrary, scripts that inject the <img> tag only when a scroll coordinate is reached (window.scrollY > 500) hide the asset from the crawler, which will see a DOM without images.

Client-side routing and URL hash management

The management of URLs in client-side applications presents a historical risk, still present today, related to the use of the hash symbol to define internal routes. Googlebot systematically ignores everything that follows the # symbol in a URL, considering it an internal fragment of the page itself (anchor link) and not an address to a separate resource.

If the site architecture relies on hash-based patterns for navigation (e.g., site.com/#/products), the search engine will only index the root of the site, overwriting and ignoring all internal variants as duplicates of the home page.

The necessary technical solution is to adopt the History API, which allows you to manipulate the URL in the address bar by creating virtual paths that are indistinguishable from static ones. This ensures that each state of the application has a unique identifier (URI) that the server can recognize and that the crawler can index separately.

The obstacles that kill your site’s Core Web Vitals

After looking at issues related to Google’s ability to find content, let’s address a different problem: the browser’s ability to display it without scaring the user away. Inefficient rendering not only makes you invisible, it makes you slow and unstable. Google severely penalizes pages that require too much CPU to render, directly affecting Core Web Vitals metrics. Here are the four technical bottlenecks you need to eliminate from your code so you don’t sabotage LCP, INP, and CLS.

- Main Thread Blocking (INP Killer)

The most common mistake is not having “too much JavaScript,” but having “JavaScript that demands precedence.” Blocking JavaScript occurs when a script stops HTML construction to be downloaded and executed. During that time, the page is frozen—and today, that’s lethal. If a user clicks and the browser is busy rendering a heavy script, the delay in response is recorded as a serious negative experience.

The operational solution:

- Break it up and defer it—strictly use defer or async attributes for all non-critical scripts. The browser needs to build the visual DOM before worrying about the chat widget or analytics trackers.

- Tree Shaking – eliminate dead code. Don’t make the user download entire libraries if you only use one function.

- Unstable layout and “naked” images (CLS killers)

Rendering is not just about the appearance of pixels, but their position. If you don’t explicitly define the dimensions (width and height) of images and banners in the HTML code, the browser doesn’t know how much space to reserve. The result? As soon as the image is rendered, it pushes down the text the user was already reading. This generates a high CLS (Cumulative Layout Shift), a sign of poor technical quality for Google.

The operational solution:

- Reserve space – always declare dimensions in the markup or use aspect ratio in CSS. Create empty “boxes” that will be filled, preventing the layout from shifting.

- Next-gen formats – abandon JPEG and PNG for WebP and AVIF formats, which offer superior compression and speed up visual rendering without losing quality.

- Critical CSS waterfall (LCP killer)

The browser doesn’t paint anything until it knows how to paint it. If your CSS file is huge (perhaps because you’re carrying around the entire unused Bootstrap framework), rendering stalls while waiting to read style rules that may only be needed in the footer. This delays the LCP.

The operational solution:

- Critical CSS inlining – extract the style rules needed only for the visible part of the screen (above the fold) and insert them directly into the HTML (<style>…</style>).

- Asynchronous loading – all other CSS must be loaded in the background, without blocking the immediate display of the title and main text.

- Hydration Mismatch in dynamic content

For sites that use frameworks such as Next.js or Nuxt (SSR/ISR), there is an insidious risk: hydration mismatch. This happens when the server sends static HTML (version A), but the JavaScript that activates on the client tries to generate different content (version B), perhaps based on local dates or user preferences. When this happens, the browser is forced to destroy the newly rendered DOM and rebuild it from scratch. For the user, this is an annoying visual “flash”; for Google, it is a sign of technical instability and a waste of resources that can lead to dynamic content being ignored.

The operational solution: ensure that the server’s HTML output is identical to what the client expects for the first paint. Handle dynamic variations (such as “Hello, Gennaro”) only after hydration is complete, or use neutral placeholders to avoid reflow.

Diagnosis and tools to unmask invisibility

The first rule for those involved in technical SEO is a healthy distrust of their own eyes. You browse the site with a powerful computer, connected to a fast network and with a browser that caches every resource; you see the images, interact with the menus, and think that everything works. But your experience is not that of Googlebot.

To diagnose rendering issues, you need to stop looking at the site as a user and start questioning it like a bot. You need to learn to see the technical discrepancy between what the server promises to send and what the browser actually manages to build. Only by isolating this difference can you understand whether you are losing traffic because of the quality of the content or because of a structural inability of the search engine to see it.

Your compass is Core Web Vitals, which we can consider, to all intents and purposes, rendering metrics—and LCP and INP are, in particular, direct diagnoses of the state of suffering of the Critical Rendering Path. Google does not penalize you for abstract “slowness,” but because the browser struggles to convert code into pixels or free up the CPU for the user.

The introduction of these metrics has definitively shifted the axis of performance measurement from network speed to rendering health. We are no longer evaluating how quickly the server responds to ping, but how efficiently the browser can convert code into a usable interface.

A correct diagnosis requires a radical change in mindset: we must stop looking at the site as it appears in our computer’s browser and start observing the technical difference between what is sent by the server and what is actually built after the scripts are executed. It is in this delta, often invisible to the naked eye but detectable by analysis tools, that the most serious positioning problems are hidden, such as content that disappears, meta tags that change, or links that are not generated because the script stops before completion.

Differential analysis: View Source vs. Inspect

Start with a manual, brutal, and immediate test that tells you the truth without the need for expensive software.

Right-click on the page and select View Source (Ctrl+U): what you see is the raw code sent by the server. Then open the developer tool with Inspect (F12): that is the final DOM, the result after JavaScript has done its work.

Compare them systematically. Look for your H1, product description, related links, or structured data. If these vital elements are present in the “Inspect” panel but are missing (or empty) in the “Source,” you’ve found the culprit. It means that content only exists if the client has the resources to generate it. If Googlebot stops earlier, that page is empty to it.

Performance diagnosis with LCP and INP

However, rendering is not just a binary issue (visible/invisible), but also a matter of measurable performance that directly impacts Core Web Vitals. As mentioned, two metrics in particular are direct offspring of your architectural choices.

The first is LCP (Largest Contentful Paint), which measures the speed of visual rendering; if you use client-side rendering, the browser must download and execute the script before displaying the main element, drastically worsening this value. Therefore, if you do not optimize CSR, you are mathematically delaying LCP because you are forcing the browser to download and execute code before it can paint the main image. Even a slow SSR (high TTFB) delays the moment when the browser receives the first useful byte.

The second and more critical metric is INP (Interaction to Next Paint), which measures the cost of rendering on the CPU. The browser has a single “thread” to work with, the Main Thread. If this thread is busy “hydrating” a complex page in JavaScript, it cannot listen to user clicks. A high INP is an unmistakable symptom of inefficient rendering that is paralyzing the device.

Tools for analysis and debugging

To isolate rendering issues, you need to use tools that see as the bot does and allow direct comparison between the source code (Initial HTML) and the rendered code (Rendered DOM).

The URL Inspection Search Console is the only source of truth for understanding what Google has rendered; by analyzing the screenshot of the scanned page and, above all, the HTML returned by the test, you can identify whether the bot stopped before loading critical content.

When you enter an address and click on “Live Test,” Google launches a real instance of its WRS. Don’t just look at the green “Available” check mark; click on “View tested page” and then on Screenshot. That photo is the trial evidence. If you see gray blocks, white areas, or exploded layouts, there’s no point in optimizing meta tags: Googlebot is telling you that it can’t render the page. At the same time, use the Rich Results Test as a “canary in the coal mine”: structured data is often the last to be loaded via JS. If the tool doesn’t detect it, it means that rendering stopped too early (timeout) and that some of the text content is probably missing as well.

Chrome DevTools also allows you to isolate the weight of JavaScript and see which scripts are blocking the Main Thread.

- Network block analysis. Open DevTools (F12), go to the Network tab, and reload the page. Filter by “JS.” Ignore the download time and the sum of kilobytes transferred, which are not the most important data; look at the “Time” column and focus on the execution latency displayed in the timeline. If you see .js files that take hundreds of milliseconds to download and execute (long green and yellow bars), you’ve found the culprits of high INP, the direct causes of Main Thread blocking.

- Code coverage. Use the Coverage tool (in the “More tools” menu of the three dots at the bottom) to quantify the waste of resources. Reload the page and look at the red bar next to each file. That bar indicates the percentage of code downloaded but not used for initial rendering. If you’re serving a 1MB bundle of which 70% is red (unused), you’re wasting Google’s render budget on dead code and functions that aren’t necessary for immediate display.

- Simulate absence. Go to the DevTools settings and disable JavaScript. Reload. What you see now is the “worst-case” experience that a crawler might have when it times out. If the menu disappears, products vanish, or text becomes unreadable, your site is not resilient and depends entirely on the goodwill of the WRS.

For large-scale analysis that goes beyond a single page, you need to use advanced crawlers. By setting SEOZoom’s SEO Spider to JavaScript rendering mode, you can scan the entire site structure by simulating the behavior of a real (Chromium-based) browser. The goal of the audit is to detect semantic discrepancies across the domain: titles that change after rendering, canonical tags that are injected via scripts, or entire sections of content that only exist in the final DOM. These differences represent points of extreme fragility, where the visibility of the site hangs on the bot’s ability to complete execution smoothly, a risk that a solid project should never take.

Tips for improving rendering

Once you’ve identified issues using these tools, you can work on practical solutions to improve performance. Some quick tips include:

- Reduce the size of static resources (images, videos, CSS, and JavaScript files) to speed up rendering.

- Optimize the loading of dynamic resources: lazy loading images, deferring scripts, and asynchronous execution of resources will help improve initial load time.

- Implement server-side rendering or static site generation to improve the load time perceived by users and promote better indexing by Google.

Understand rendering for smoother experiences

Your site’s ability to be “read” by machines is the biological prerequisite for visibility.

You can have the most refined content marketing strategy in the world, but if your technical architecture forces Google to struggle to see your work, you’re running with the handbrake on. Never assume that human visualization corresponds to algorithmic understanding. Constantly check the differences between source and DOM, choose an architecture that minimizes client-side risk, and remember: the battle for positioning is won before the user even arrives on the page; it is won the moment the server responds.

Ultimately, don’t leave it to chance whether Google sees your content. Choose the architecture that minimizes risk (SSR or Hybrid), monitor the differences between source code and rendered DOM, and remember: if Google can’t render it, it doesn’t exist for the market.

Answers to the main FAQs about rendering

In conclusion, here is a list of frequently asked questions designed to answer the real doubts that block entrepreneurs and SEO specialists, going beyond simple technicalities.

- What is rendering?

Rendering is the process by which a browser transforms the code of a web page (such as HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) into visual elements that the user can see and interact with, such as images, text, and layout. It is the stage that makes the content of a site visible directly on the visitor’s screen.

- What is the difference between crawling, rendering, and indexing?

These are three distinct phases that are often confused because they occur in sequence, but they produce different effects. Crawling is used to discover the URL and download the source code. Rendering is when that code is processed and executed, transforming it into a structured page with defined content and hierarchies. Indexing comes after and concerns what Google has actually “seen” and understood after rendering. If part of the content only emerges later, or in an unstable way, it enters the process in a reduced or distorted form.

- What are rendering engines and which are the most popular for browsers?

The rendering engine is the browser software component that translates raw code into pixels visible on the screen. Without it, the web would be just a long list of incomprehensible text.

Today, the market is dominated by three large “families,” and knowing them is vital because if your site has a bug on one of these engines, you are cutting out a specific slice of users (and bots).

- Blink: is the absolute giant. Born as a derivative of WebKit, today it is the engine of Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Opera, Brave, and Vivaldi. If you optimize for Blink, you cover the vast majority of global traffic.

- WebKit: this is the guardian of the Apple ecosystem. It is the exclusive engine of Safari (both on macOS and iOS). Technical note: on iPhone and iPad, all browsers (including Chrome for iOS) are forced to use WebKit under the hood, so if a site “breaks” on iPhone, it is almost always due to a lack of optimization for WebKit.

- Gecko: the historical alternative. It is the open-source engine developed by Mozilla for Firefox. It stands as an independent bulwark against the Blink/Chromium monopoly.

- EdgeHTML [Obsolete]: we mention it only for the sake of historical record. It was the proprietary engine of Microsoft Edge, but today it has been abandoned because Microsoft has switched to Blink to ensure maximum compatibility.

For modern SEO, it is crucial to know that Googlebot and AI crawlers (such as ChatGPT) use “headless” versions of Blink: if your site has rendering issues on Chrome, it will also be mathematically invisible to search engines and generative responses. Therefore, optimizing for Blink is not just about pleasing users, but ensuring that your content is readable by new generative response engines.

- How do rendering engines work?

The work of a rendering engine follows a three-step cyclical process that transforms invisible code into a visual experience:

- Input decoding (Parsing): the engine takes the source code (HTML and CSS) and scans it line by line to identify the “building blocks” of the page – blocks of text, images, scripts, and style instructions.

- Data processing (Construction): it reprocesses this information to build an internal logical map (the Render Tree) that establishes not only what should appear, but where and how (calculating dimensions, positions, overlaps, and colors).

- Graphical representation (Painting): Finally, working with the GPU (graphics card), it transforms this abstract logical map into actual pixels on the browser screen, materializing the final page that the user can view.

- Does Google see the page as the user sees it?

No. Google builds a representation that is functional for understanding, not a faithful replica of the visual experience. The user’s browser works in real time, with local resources, cache, interactions, and progressive fallbacks. Googlebot, on the other hand, operates with different priorities, time limits, and a pipeline designed to classify, not to navigate. The page “seen” by the engine is a structural summary, not an aesthetic rendering.

- Does rendering only affect sites that use JavaScript?

JavaScript amplifies the problem, but it doesn’t create it on its own. Even seemingly simple sites can have rendering issues if they load content asynchronously, change the page structure after the initial load, or depend on slow external resources. The point is not the technology used, but when and how content becomes available in the processing flow.

- Google says it “can read JavaScript.” Why should I worry?

Google can read JavaScript, but it doesn’t promise to always do so immediately. Rendering requires enormous resources. If your site is small and fast, you’re probably safe. But if you have thousands of pages or complex scripts, relying on the “goodwill” of the WRS (Web Rendering Service) means accepting that many of your pages will remain in the rendering queue for days, or be ignored if the timeout expires first.

- Can Googlebot index sites entirely in JavaScript?

Technically yes, but not instantly or unconditionally. Googlebot executes JavaScript using an infrastructure called Web Rendering Service (WRS) based on a headless version of Chrome. However, unlike static HTML, which is read immediately, JavaScript requires high computing resources and is often placed in a rendering queue (Render Queue). If the script takes too long to execute, generates errors, or exceeds the render budget allocated to the site, the process times out. As a result, Google may only index the empty shell of the page, ignoring the dynamically generated content. Blindly relying on Google’s ability to execute all code is a high-risk strategy.

- Does Google always execute all JavaScript on a page?

No. Script execution depends on priority, complexity, and available resources. Some scripts are postponed, others are partially executed, and still others are ignored if they are not considered essential. This means that a page may be formally accessible but semantically incomplete. The engine works on what it can reliably process, not on what the site “intends” to show.

- What is the difference between Server-Side Rendering (SSR) and Client-Side Rendering (CSR) for SEO?

The difference lies in who bears the computational load and, consequently, in the risk of indexing. In Server-Side Rendering (SSR), the server processes the code and sends a complete, ready-to-use HTML to the browser; this ensures that Googlebot immediately sees the content without having to execute scripts. In Client-Side Rendering (CSR), the server sends a blank page and delegates the task of downloading and executing JavaScript to build the interface to the device (or bot). CSR is dangerous for SEO because it introduces breakpoints: if the bot does not have the resources to complete the execution, the page remains invisible. SSR is an insurance policy on visibility, while CSR is a gamble on crawler performance.

- Why does the Search Console URL Inspection tool show a different page than the one I see in my browser?

The “URL Inspection” tool shows exactly what the WRS was able to render within its time and resource limits. If you see discrepancies, such as missing text or empty blocks, it means that the rendering process was interrupted before completion. This often happens because your desktop browser has much more computing power than the bot, allowing it to run heavy scripts that instead cause the crawler to crash. That partial image in Search Console is the only truth that matters for ranking: if the content isn’t there, it doesn’t exist for the algorithm.

- Does using frameworks such as React or Angular penalize ranking?

It is not the technology itself that penalizes, but its implementation. Modern frameworks tend to handle navigation and content through client-side logic that can obscure the site structure to crawlers. Common problems include the use of simulated links via onclick events instead of standard <a> tags (which interrupt the PageRank flow) or slow hydration that worsens the INP metric. When configured in SSR mode or using Static Site Generation (SSG) techniques such as Next.js or Nuxt, these frameworks can produce perfectly optimized sites. The problem arises when they are used in pure Single Page Application mode without considering crawlability requirements.

- How does rendering affect Core Web Vitals?

Rendering is the direct technical cause of the performance measured by Core Web Vitals. Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) measures visual delay: client-side rendering pushes back the moment the user sees the main content, worsening the score. Interaction to Next Paint (INP) measures the cost of execution: if the browser’s Main Thread is clogged with heavy JavaScript execution (typical of the hydration phase), the page cannot respond to user input. Optimizing rendering means freeing the CPU from unnecessary tasks, directly improving these metrics and the related ranking.

- Can a page be indexed but misinterpreted?

Yes, and it is one of the most common cases. The URL enters the index, but the content is classified poorly because the structure emerges in a confusing way, the main text arrives late, or the information hierarchy is unclear. In these cases, the page exists but struggles to compete because it does not clearly communicate its central theme.

- How can you tell if a ranking problem is due to rendering?

The signs are never isolated, but recurring. Pages that struggle to rank despite solid content, unstable results on consistent queries, and marked differences between what is visible to the user and what emerges in analysis systems are clues to be read together. When the content is there but doesn’t “come across,” rendering is often part of the explanation.

- Does rendering affect the crawl budget?

Absolutely. A site that requires heavy client-side processing consumes much more of Googlebot’s machine time. If the bot takes 500ms to render your page instead of 50ms, it will be able to crawl far fewer pages of your site in the same amount of time. Optimizing rendering (by switching to SSR or SSG) is the most effective way to increase the number of pages indexed daily.

- My site is slow to load: does that mean I have rendering issues?

Not necessarily, but they are often related. A slow site for the user (high LCP) suggests that the browser is struggling to process the code. If this struggle is due to too many JavaScript files blocking the Main Thread, then yes: you have a rendering issue that is killing both the user experience and Google’s ability to crawl your site.

- I changed the graphics and traffic plummeted. Could rendering be to blame?

It’s the number one suspect. If the redesign introduced frameworks such as React or Angular without providing for Server-Side Rendering (SSR), you may have made the content invisible to bots. Check immediately if the text of the new pages is visible in the source code (Ctrl+U): if it’s not there, Google has stopped reading you.

- Do I have to abandon React or Vue to do SEO?

No, you don’t have to change technology, you have to change architecture. React and Vue are excellent, but by default they use Client-Side Rendering (CSR). You need to configure them to use Server-Side Rendering (with frameworks such as Next.js for React or Nuxt.js for Vue) or static generation. The problem is not the language, it’s who executes the code

- Why do I see blank screens in Search Console’s “Live Test”?

That is the definitive sign that rendering is failing. It means that the resources needed to draw the page (often critical JS or CSS files) are blocked by robots.txt, have timed out, or require too much CPU. As long as you see white there, you are invisible in SERP.

- Should structured data (Schema.org) be placed in static HTML?

That is the recommended practice. If you inject it via JavaScript (e.g., with Google Tag Manager), it only works if the rendering is successful. Since Rich Snippets are a huge competitive advantage, entrusting them to an uncertain process is an unnecessary risk. Put them in the server-side code to ensure that Google sees them right away.

- What is the Hydration Gap?

It is that annoying phenomenon where the page appears to be loaded (you can see the text), but when you click on a button, nothing happens for a couple of seconds. This happens when the browser has to “hydrate” the static HTML by linking interactive scripts to it. It’s not a big deal for Googlebot (it doesn’t click), but for Core Web Vitals (especially INP) it’s devastating and can penalize you on the UX side.

- Does rendering also impact automatic response AI systems?

Yes, because those systems work on what they can extract cleanly and consistently. If rendering produces a fragmented page, with main content that is unstable or difficult to isolate, the likelihood of that information being selected or synthesized decreases. Structural clarity becomes a prerequisite, not a technical detail.

- Do ChatGPT and Perplexity read JavaScript sites?

Much worse than Google. Many AI bots use simplified headless browsers to save costs (token economy) and often do not execute complex JavaScript. If you want to be cited as a source in generative responses, providing clean, static HTML is almost mandatory. AI favors immediate readability (Machine Readability).

- Do new AI-based search engines (such as Perplexity or ChatGPT) handle rendering like Google?

No, they are much more rigid. RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) engines must read and understand content in real time to generate a response to the user. They do not have the deferred “rendering queue” mechanism that Google uses. They have very low execution timeouts, in the order of milliseconds. If the page does not provide textual content immediately (as is the case with SSR or static HTML), these bots abandon the scan and discard the source. An architecture that takes seconds to load content via JavaScript automatically cuts the site out of AI-generated responses.

- Is Edge Rendering only for huge sites?

Not anymore. With services such as Cloudflare Workers or Vercel, Edge Rendering is accessible to everyone. It is particularly useful if you have an international audience: rendering the page on the CDN node closest to the user (in Milan for an Italian user, in New York for an American user) guarantees incredible speed and a very low “Time to First Byte,” which Google loves.

- Is rendering a technical or strategic issue?

It’s both, but with a growing emphasis on the strategic side. It’s not just about how the page works, but about the ability to control how content is interpreted, classified, and reused. In a web where visibility increasingly depends on selection and synthesis, governing rendering means governing access to meaning.

- What happened to Dynamic Rendering? Is it still worth using?

Short answer: no. Consider it a patch, not a strategy.

Full answer: until a few years ago, Google suggested Dynamic Rendering as a stopgap solution for JavaScript-heavy sites. The logic was simple: the server recognized who was visiting the site (User-Agent Sniffing). If it was a human user, complex JavaScript (CSR) was needed; if it was Googlebot, a simplified, pre-rendered static HTML version was needed.

Today, this practice is officially considered a temporary workaround and not a long-term solution. There are three reasons for this:

- Complexity and costs. Maintaining two separate versions of the site (one for humans, one for bots) doubles testing and maintenance costs.

- Cloaking risk. If the HTML version for the bot differs too much from the one for the user (perhaps because you forget to update it), you risk a penalty for cloaking, one of the “oldest” Black Hat SEO tactics.

- Technological evolution. With the advent of modern SSR, ISR, and Edge Rendering, there is no longer any technical reason to use this trick.

If you have a legacy site that already uses dynamic rendering, you don’t have to turn it off tomorrow morning, but your goal for 2026 should be to migrate to a native server-side or hybrid architecture. Never start a new project today based on dynamic rendering.